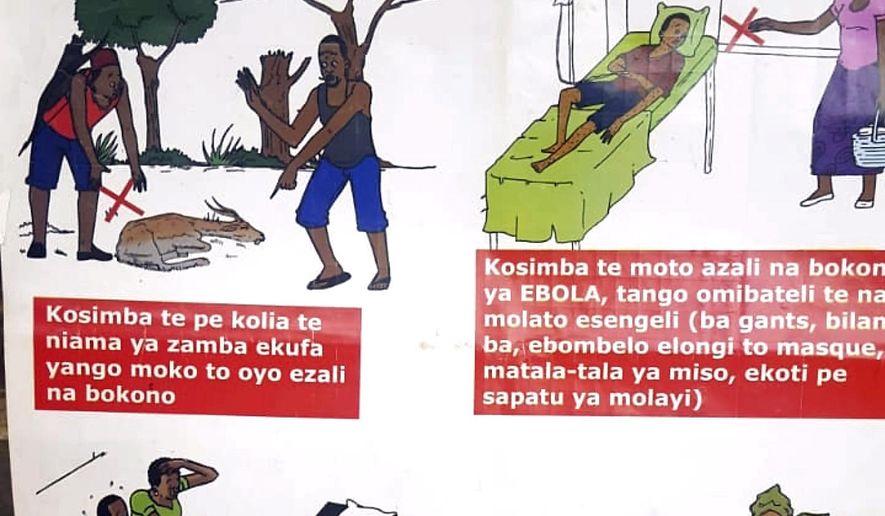

As world health officials respond to a growing Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, they are expressing concern that public education about the disease is having little effect.

Congo health officials are encouraging people to wash their hands, to touch each other as little as possible and to avoid meat that is potentially infected, Al Jazeera reported. But men captaining small rowboats along the River Congo said in interviews that they know little about the disease and put their faith in God to protect them.

Health officials are concerned that the proximity of the outbreak to the river, a main thoroughfare that runs through four countries, will carry the disease into more communities that are unaware of how it spreads and how to protect against it.

This is the 11th Ebola outbreak in the Congo, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It was confirmed May 8, and has grown to include 45 infected and 25 dead.

The disease is spread through direct contact with contaminated bodily fluids of an infected person or of the fluids from an infected animal, most typically a bat.

Among the reasons Ebola spread fast across West Africa during the 2014 outbreak — killing more than 11,300 and infecting 28,000 — was a lack of public knowledge about how the virus is transmitted and what the people can do to protect themselves.

Symptoms can appear mild at first, surfacing on average between eight and 10 days after first contact. These include fever, headache, muscle pain, weakness and fatigue and become more serious — diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain and unexplained bleeding or bruising.

That outbreak, the largest of its kind, spread to Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea.

In Liberia, health workers identified ritual burial practices as greatly fueling the spread of disease, with whole families or villages wiped out as infection jumped from the deceased to those who tried to bury their loved ones with dignity.

While burning bodies was the most efficient way to kill disease, this outraged Liberians, who viewed it as desecration and then hid and buried the bodies in secret.

Global Communities, a U.S.-based nonprofit that responded to the Ebola outbreak, said in a 2015 report that burial rituals and traditions increased infection rates by nearly 70 percent, with caretakers and families often sleeping in the same room as the body overnight and washing the body and themselves using the same water.

The organization responded by setting up designated burial sites and had volunteer workers with protective gear carry out ritual practices. In the early days, volunteers were often met with hostility among villagers and had to work to gain trust that their work was helping save lives.

At the peak of its activities in October 2014, Global Communities managed safe burial sites across all 15 counties in Liberia with a team of more than 500 workers.

As the outbreak largely came under control at the end of 2015 in Guinea, CDC researchers found that public education and knowledge surrounding Ebola reached about 92 percent of the population. These people knew that more frequent hand washing, limited physical contact with suspected infected persons and taking precaution around burials were all preventive measures against the spread of disease.

Yet a “substantial percentage of participants harbored misconceptions” about transmission and treatments, the authors wrote in their report, with half of respondents believing Ebola is transmitted by mosquitoes or through the air.

People also feared being close to Ebola survivors, distrusting that their “cured” status was a lie by government authorities.

“These data underscore the value of ongoing health promotion efforts to prevent sporadic transmission or future outbreaks including messaging that aims to reverse misconceptions about Ebola transmission and prevention, to clarify duration and modes of transmission from survivors, and to address stigma that survivors might face as they recover, rebuild their lives, and reintegrate into communities,” the authors wrote.

In Sierra Leone, the U.S.-based non-profit Humanity and Inclusion, ran a targeted education campaign so that 1,700 children with disabilities knew how to protect themselves from contracting Ebola, an already marginalized community the organization was working with to increase access to education.

“At first, my work was difficult because many people did not want to believe that Ebola was real,” Sheku Kamara, an H.I. volunteer, said in a statement. “However, we developed a dialogue system with rules and regulations that made sense to the people, and they listened.”

When the government closed schools around the country to protect against the spread of infection, H.I. volunteers and workers went door to door to homes with children with disabilities and educated them on the importance of hygiene and provided washing materials.

When schools re-opened they worked to provide hand washing stations and checked in with students that they understood the importance and steps necessary to prevent the spread of disease.

“I’m very proud to say that none of the children in my area got sick. We kept Ebola away,” Mr. Kamara said.

• Laura Kelly can be reached at lkelly@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.