A Never-Before-Seen Virus Has Been Detected in Myanmar’s Bats

The discovery of two new viruses related to those that cause SARS and MERS marks PREDICT’s first milestone in the region

:focal(52x364:53x365)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0b/cf/0bcfb9df-cc12-4c11-b49e-d244c3d83c3c/global_health_program_staff_holding_a_wrinkle-lipped_bat_mg_1960.jpg)

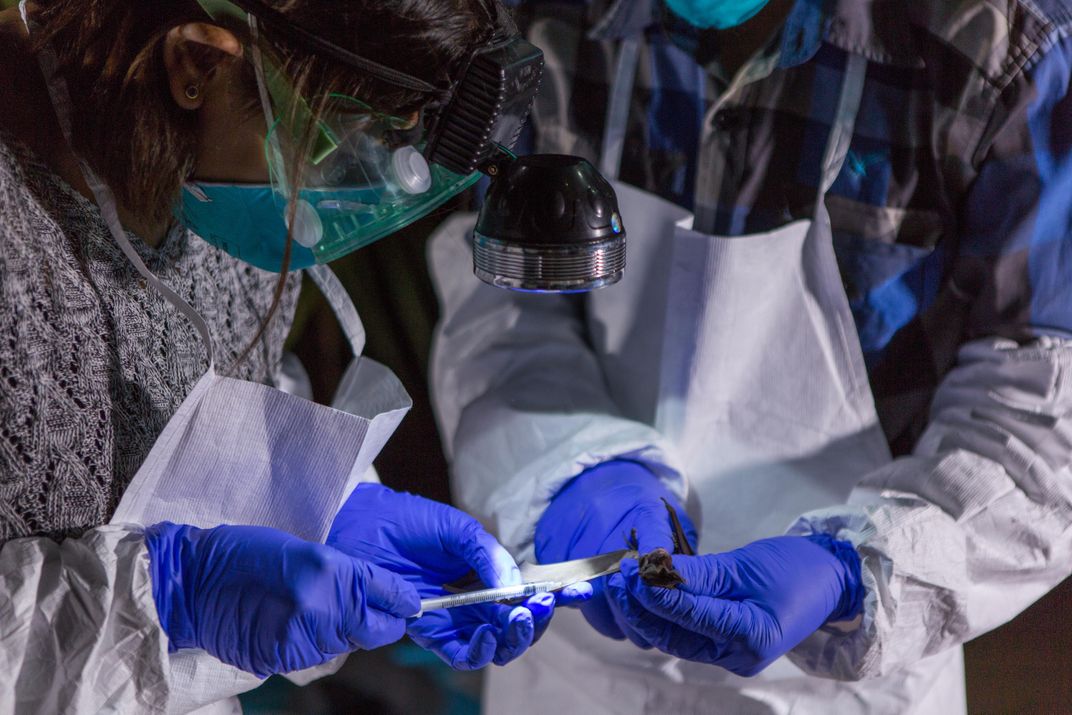

To prevent the next pandemic, pinpoint it at the source. That’s the idea behind PREDICT, a global surveillance program that has spent almost 10 years hunting for new viruses that could spill over from vulnerable wildlife to humans. Now, PREDICT researchers in Myanmar have hit pay dirt with a never-before-seen virus that infects wrinkle-lipped bats—a virus in the same family as the ones that cause SARS and MERS.

The Myanmar virus is the first of its kind to be detected on a global scale. The team additionally identified a second new virus that had previously been found in Thailand, also in bats. Such discoveries are critical, because what happens in Myanmar doesn’t always stay in Myanmar. “Myanmar is in a central location in Southeast Asia—an area of primary concern for viral diseases and emerging infectious disease,” says Marc Valitutto, a wildlife veterinarian heading the efforts in the region, which is lush with tropical rainforest and rich in biodiversity.

Around 75 percent of today’s emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic, or transferred by contact between wildlife and humans. But because animals don’t always exhibit—let alone complain of—the same symptoms of illness that humans do, zoonotic diseases are challenging to detect, and the consequences can be disastrous. Since the turn of the 21st century, more than a dozen global outbreaks have spread from animals to humans, including Ebola, SARS and avian influenza.

With this in mind, the PREDICT team has leveraged the veterinary resources at the Smithsonian to unveil potentially devastating diseases that have not yet entered the human population. Their efforts, which span the fields of wildlife conservation and global public health, bolster the world’s growing arsenal against infectious disease. PREDICT is funded by USAID, and brings together a bevy of global health-minded organizations including the Smithsonian Institution, the One Health Institute at the University of California at Davis, EcoHealth Alliance, Metabiota and the Wildlife Conservation Society.

In many cases, the team ends up turning first to wildlife: “Human health is critical, but if you want to get upstream of an outbreak, you need to think increasingly about where the virus is coming from and how you can detect it,” explains Suzan Murray, director of Smithsonian’s Global Health Program, which partners with PREDICT in Myanmar and Kenya.

So far, the team has discovered over 800 new viruses globally by sampling local wildlife, livestock and human populations susceptible to transmission in over 30 countries in Africa and Asia. But according to Chelsea Wood, a conservation ecologist at the University of Washington who is not affiliated with PREDICT, this is likely only the tip of the iceberg. “People really overestimate our understanding of medically important viruses in the world,” she says. “Tropical rainforests [in particular] are just cesspools of viral diversity—the highest viral diversity on the planet.”

To make this latest discovery, Smithsonian conservation biologists spent three and a half years closely tracking the bats, primates and rodents—animals previously implicated in the spread of viral epidemics—native to Myanmar. Each animal that comes under the care of the Myanmar team undergoes extensive testing, with researchers collecting saliva, urine, feces and blood. Valitutto and his team have also begun to track the migration patterns of several bat species in the area using cutting-edge GPS technology. “If one species carries a disease, it’s important to know where it’s going and where it’s coming from,” Valitutto explains.

According to Tracey Goldstein, associate director of the One Health Institute, only about 1 to 3 percent of samples contain viruses of interest—that is, viruses within target families known to cause disease. An even smaller fraction are related enough to pathogenic strains to qualify for further study, such as the two new viruses in Myanmar. These, however, are the viruses that have the most potential to threaten human populations. Once these specimens come into their hands, Goldstein and her colleagues assess their ability to infect a range of animal and human cells.

While both of the new viruses are related to viruses that have previously caused deadly epidemics in humans, researchers stress that the relationship is distant, so it’s possible neither will pose any imminent threat. However, every newly identified virus contains critical information, regardless of its ability to move into human populations. “These new viruses in Myanmar may fall lower on the priority list because they’re not very closely related to something we care about,” Goldstein says. “But they’re also important to understand the differences between viruses that can and can’t infect humans.”

Over 1500 additional Myanmar samples await processing, which will be carried out in labs in both Myanmar and the United States. A primary goal of PREDICT is to equip local laboratories in host countries with the resources and expertise to eventually independently acquire and process samples, so that the work may continue even after the programming concludes. Globally, over 3300 government personnel, physicians, veterinarians, resource managers, laboratory technicians and students have been trained by PREDICT.

The surveillance program also emphasizes local community engagement and aims to support a sustainable health infrastructure informed by their discoveries. All relevant results are ultimately passed on to each country’s ministry of health to help shape future changes in policy. The information is then distilled to the public in a culturally cognizant manner, coupled with recommendations to minimize risky behaviors, such as consuming bush meat or bringing live animals to market, that might facilitate the spread of disease.

“The program is truly encompassing of the One Health concept,” says Valitutto. “It involves animal disease and animal health, human health and environmental health. We as a project are able to speak to three different areas.”

Although the ultimate aim of PREDICT is to avert future pandemics in the human population, Valitutto and Murray emphasize the importance of supporting the health of wildlife at the interface between animal and human. When animals win, we win. And while species like bats are capable of harboring disease, they also confer enormous ecological benefits, including pollination and pest control, according to Angela Luis, a disease ecologist at the University of Montana who is not affiliated with PREDICT.

“All of these viral discovery studies are concentrating on specific animal species, but it can often lead to us demonizing these species,” Luis says. “Just because they carry nasty diseases doesn’t mean we should kill these species.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)