Column: Anti-vaccine stupidity returns, as measles cases rise and California parents evade the law

California struck a blow for intelligent public health policy in 2015, when the state abolished all “personal belief exemptions” from child vaccine mandates.

The new rules were designed to put a stop to the stupid and irresponsible behavior of parents whose casual approach to getting their children vaccinated against a host of communicable diseases — chiefly measles, mumps and rubella — places their neighbors’ children and their entire communities at risk.

The new policy bore almost immediate fruit, as its sponsor, state Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), recently wrote in the journal Pediatrics. (Pan is a physician.) But Pan also reported that some parents who took advantage of personal exemptions in the old days have found a way to circumvent the rules — and some California doctors are helping them. Personal exemptions have all but disappeared, but medical exemptions are on the rise. As my colleague Karen Kaplan reports, many of those medical exemptions are bogus.

The point isn’t to punish your child or your family — it’s to protect other children.

— State Sen. Richard Pan

The statistics on medical exemptions come from a study, also published in Pediatrics, which found that personal belief exemptions have been eradicated but medical exemptions are on the rise. Not all of these are fake, but the total is higher than can reasonably be expected. (My colleagues Soumya Karlamangla and Sandra Poindexter spotted this trend in its infancy last year.)

Pan reports that a rise in medical exemptions had been expected after the crackdown on personal belief exemptions, because many families eligible for medical exemptions had opted for personal belief exemptions, which didn’t require the same level of paperwork. But the surge has taken public health officials by surprise. “MEs more than tripled,” he writes, with some schools reporting medical exemption rates higher than 20%, “revealing that many students received inappropriate MEs.”

What’s especially alarming about this finding is that cases of measles are again on the rise in the U.S. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports 142 cases as of Oct. 6, the highest figure since the 188 cases in 2015; if current trends continue, the caseload could exceed that figure to become the highest since the outbreak of 667 cases in 2014. The CDC reported 11 individual outbreaks in 25 states and the District of Columbia. The majority of sufferers were unvaccinated. Among the most severe outbreaks is in Rockland County, N.Y., which has recorded 33 cases and asked unvaccinated pupils to stay home from school.

The trend line even prompted Scott Gottlieb, commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, to warn via Twitter that measles “puts young children at significant risk.” He connected the spate of outbreaks and the risk of a worsening spread of the disease to “debunked skepticism of MMR vaccine and our negligent accommodation of those theories.”

Gottlieb’s reference is to the handiwork of Andrew Wakefield, a British physician who lost his license for fraudulently promoting a nonexistent link between the MMR vaccine and autism. His claim has been utterly discredited, but still is capable of gaining the attention of credulous individuals like Jenny McCarthy and Donald Trump.

California’s experience with tightened vaccination regulations demonstrates their effectiveness and the remaining challenges. Pan’s Senate Bill 277 eliminated nonmedical exemptions for vaccination as a prerequisite for school attendance. In 2014-2015, only 90.4% of California kindergartners were fully immunized, below the 94% judged to be the minimum to confer “herd immunity,” or to protect even those who couldn’t be immunized for legitimate reasons.

After the measure was signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in 2015, according to researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, Johns Hopkins, and Emory, the proportion of California kindergarten students reported to have received all required vaccines increased from 92.8% in 2015–2016 to 95.1% in 2017–2018.

But the proportion of pupils receiving medical exemptions rose to 0.7% from 0.2% — with the sharpest increases tending to occur in districts that previously had been hotbeds of personal belief exemptions. That led the researchers to conjecture that the increase was due in part to “the willingness of some physicians to write medical exemptions for parents who are vaccine hesitant [but] whose children may lack scientifically justified medical contraindications.”

Pan acknowledged that SB 277 made no changes in the law related to medical exemptions, which gives the authority to licensed physicians who turn over the paperwork to parents for submission directly to school boards.

That’s an imperfect arrangement, Pan says. “Granting MEs to legally required vaccines is not the practice of medicine but a delegation of state authority to licensed physicians to protect public health and individuals. Essentially, physicians are fulfilling an administrative role.”

It’s also a problem for state and county public health officials, who have no way to gauge whether the authority is being abused by individual doctors, and for state medical regulators, who have little ability to ferret out abusers. The Medical Board of California, as Pan told me, “generally acts on the basis of complaints from patients.” In these cases, however, “the patient’s family is in cahoots with the medical provider” — vaccine resisters aren’t likely to file complaints against the doctors who gave them what they wanted. If the board wished to discipline a doctor for issuing bogus exemptions, it would have to go to court to obtain patient records, a lengthy, costly and uncertain process.

Indeed, the Pediatrics researchers found that among health officers they interviewed, “many participants wanted the California Medical Board to take a more active role in disciplining physicians who were writing medical exemptions that they perceived to be problematic.” The Medical Board told the researchers, however, that a majority of the 60 complaints it had received about bogus medical exemptions since the advent of SB 277 had been closed “because of no violations being found, insufficient evidence to pursue disciplinary action, or the inability to proceed because of a lack of supporting evidence.”

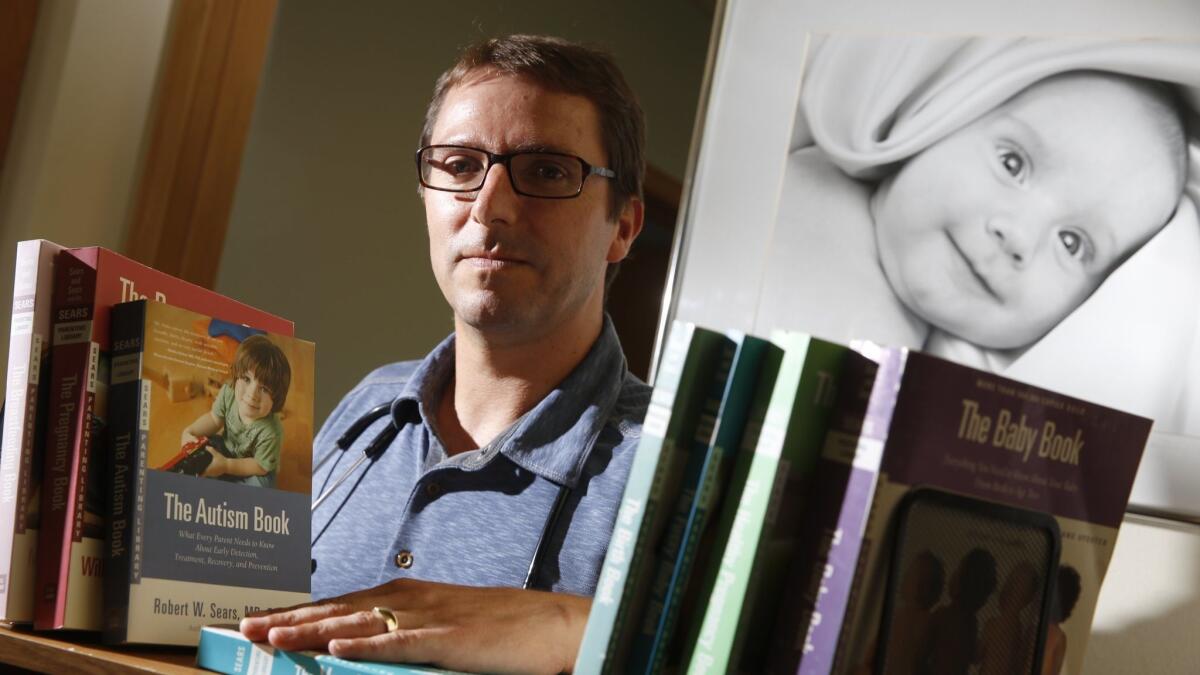

The most notable exception was the discipline imposed on Orange County pediatrician Bob Sears, a well-known facilitator of vaccine resistors who was slapped this year with 35 months’ probation for issuing a medical exemption for a 2-year-old boy without first conducting an exam. “Hopefully that’s a reminder to physicians that what some of them are doing is unprofessional and would have consequences,” Pan says.

One legislative solution would be eliminating the authority for doctors to issue exemptions on their own, placing it instead in the hands of local or state health officials — they’d examine the doctor’s finding, then decide whether to issue the exemption. That also would give the officials the data they’d need to identify the sources of excessive exemptions, which they could then pass on to the medical board for disciplinary action.

That change would require legislation. Pan says that may be in the offing, but he’s reluctant to act just yet, partly because SB 277 generally has worked well. If the rate of medical exemptions continues to rise, however, placing communities again at risk, legislation may be needed — perhaps giving health officials the authority to invalidate medical exemptions and to publish lists of doctors whose right to issue them has been revoked.

“People need to remember that the purpose of our vaccination laws is to keep all children safe at school,” Pan says. “The point isn’t to punish your child or your family — it’s to protect other children. The purpose is to protect children who are vulnerable to these preventable diseases. Part of our duty as members of society is to help protect each other. That’s why we have these requirements. It’s about keeping kids safe.”

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.