Barbara Bramanti grew up near Florence, Italy, worked for a while in Mainz, Germany, and is now at the University of Oslo in Norway. Her career has taken her across a decent swath of Western Europe—but not nearly across as big of an area as that ravaged by the plague she studies.

In her latest work, she and her colleagues associate Europe's Black Death plague outbreak with a change in trade policy in Asia.

Where’d they come from?

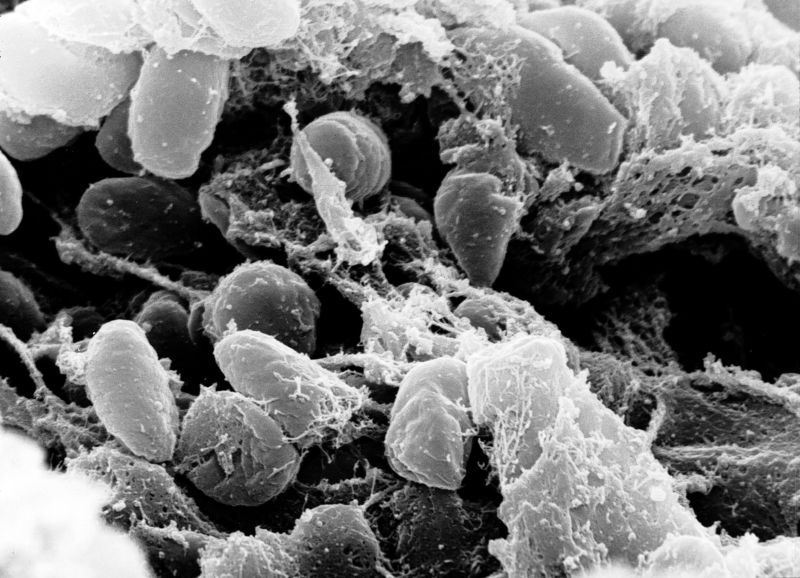

Yersinia pestis, the subject of her research, is the bacterium responsible for three bubonic plague pandemics over human history. The first was the Justinian Plague, which started in Constantinople around the year 541 CE and devastated the Byzantine Empire until the middle of the eighth century. The second began with the Black Death, which killed at least 30 percent of the population of Western Europe between 1346 and 1353 and then continued rampaging over the next 400-ish years. The third started in 1772 in Yunnan Province, in Southwest China, and is still currently underway.

The origin of the second Medieval epidemic and the routes by which it was transmitted are as yet unclear. Plague is zoonotic, meaning it can hang out in animal reservoirs until it jumps into human populations. The hosts in which it may have bided its time in Western Europe between outbreaks is unknown; thus, it is possible that Y. pestis didn't hang out in reservoirs there at all over the centuries. Instead, it may have been reintroduced multiple times from a reservoir farther East. Different historians have proposed these two mutually exclusive scenarios, and Bramanti hoped that a genetic analysis could distinguish between them.

She and her group sequenced five new plague genomes from 14th century skeletons in Italy, France, Holland, and Norway. They also reanalyzed previously isolated plague samples so they could confidently compare the samples, knowing that any DNA differences they found were not a result of different methodologies or lab conditions.

The bacteria they found in France and Norway was the same as that previously identified in London and Barcelona as responsible for the Black Death there (with the caveat that they didn't sequence the entire genome; all of the DNA that was analyzed was identical). The Italian variant, taken from a mass grave, had sequences that dated it as a more recent strain than the others. Bramanti thinks that this strain came from overseas through the port of Pisa and acquired its new sequences as it scythed through Tuscany in 1348.

The Russian connection

The Dutch clones seem to be related to those previously isolated in London as well as in the Russian city of Bolgar. Bolgar's marketplace was thriving in the 1340s and '50s, but it was destroyed by a fire at some point in the 1360s or '70s. Archeologists have found Flemish artifacts at the site, indicating an active trade with Western Europe. If goods were being transmitted back and forth between these regions in the 14th century, bacteria likely were as well.

These genetic analyses, along with climatic studies done by Bramanti's colleague Nils Stenseth, all argue that Yersinia pestis entered Western Europe from Asia repeatedly during the second plague pandemic rather than hanging out in Western European rodents the whole time. This plays into Bramanti's pet theory that the bugs hitched rides with fur traders.

"During the 14th century, Russia was under the domination of the Golden Horde, which had imposed new regulations on the fur trade," she writes. In the 1340s, the Horde supported a new overland route that resulted in a lot of fur moving from the "Land of Darkness" along the Kama River, westward to Black Sea ports. This jibes chronologically with the onset of the Black Death; and plague could have continued traversing this route with the fur traders for centuries.

PNAS, 2018. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1812865115.aaq0620 (About DOIs).

reader comments

43