El Niño is back—although it probably won’t be the monster it’s been in the past.

In an announcement last week, NOAA noted that while the southern half of the United States may see wetter conditions in the coming months, this year’s event is likely to be weak and probably won’t come with any significant global impacts. There’s about a 55 percent chance it will last into the spring, according to NOAA forecasters.

That’s in stark contrast to the last El Niño event, which ended in 2016 and is considered one of the strongest in recent records.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

El Niño events tend to be diverse: A severe event one year doesn’t necessarily suggest the next one will be as intense. In the long term, though, scientists suggest that El Niños—or, at the very least, their effects on weather and climate events around their world—may become more severe as the planet continues to warm.

By definition, El Niño is one phase of a major natural climate phenomenon known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, which involves shifting patterns of warming and cooling in the Pacific Ocean. The other phase, La Niña, is considered the cool phase.

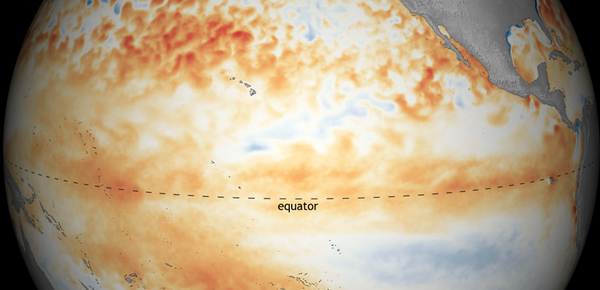

El Niño, the warm phase, typically kicks off during the winter months with a pattern of above-average sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific, usually concentrated either in the central or eastern part of the ocean. The exact triggers are still a little murky to scientists but are typically associated with a temporary shift in certain wind patterns over the ocean.

Because ocean and atmosphere are so tightly linked—heat and moisture is transferred between them—the warming of the seas drives a variety of predictable weather and climate patterns around the world.

Countries in South Asia may experience higher temperatures. A wide swath of the tropical Pacific sees increased rainfall, while places like Australia may dry out. In the United States, the southern half of the country often sees an increase in storms and severe weather outbreaks.

These kinds of shifts mean certain locations around the world may become temporarily more prone to events like droughts, floods, landslides, tornadoes, heat waves and other disasters.

According to Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, one of the few things that can be said with any real certainty about future El Niños is that their side effects will probably become more severe, wherever they occur—even if the El Niños themselves don’t really change much.

In other words, an El Niño event of the exact same magnitude 50 years into the future—typically defined by the amount of temporary sea surface warming it involves—is likely to produce more severe weather consequences than might be seen today.

That’s because the local influence of global warming in the places where these events occur is likely to compound the natural influence of El Niño.

“El Niño causes floods and droughts in different places around the world and is the main cause,” Trenberth said in an email to E&E News. “Those clearly get worse or stronger with global warming.”

A paper published last August in Geophysical Research Letters found that model simulations support this idea. If a given El Niño event occurred now, and then again 100 years from now after 7 or 8 degrees Fahrenheit of global warming, the heat waves and wildfires associated with the future El Niño event would be worse.

“What we’re seeing is that because of this overall warming of the land surface, for an El Niño of a given strength, the effects on the wildfire initiation and length and things like that are going to become stronger in the future,” said Samantha Stevenson, a climate scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara and one of the paper’s co-authors.

She added: “Because you’re gonna have just a drier, warmer climate—and if you add a dry, warm anomaly on top of that, that’s going to have an enhanced impact on things like wildfires.”

The uncertain future of El Niño

Whether El Niño events will actually change in the future is a more uncertain question, according to Trenberth. But some research suggests severe El Niños, like the 2015-2016 event, may happen more frequently as the climate warms.

Wenju Cai, a climate scientist at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, has published several studies suggesting this may be the case.

His most recent, just published in Nature in December, looked at the variations in Pacific Ocean surface temperatures under a “business-as-usual” climate scenario, which implies 7 or 8 F of warming by the end of the century.

The study found that future El Niño events will involve bigger temperature variations in the eastern tropical Pacific. In other words, there’s the potential for much hotter temperature anomalies in the ocean when El Niño occurs.

The paper “goes to the heart of the question” about future El Niños by looking directly at sea surface temperatures, Cai told E&E News. Because Pacific Ocean temperatures tend to drive the other weather and climate consequences of El Niño around the world, the study implies that “strong” events will occur more commonly in the future.

In two previous papers, published in 2017 and 2014, Cai and colleagues also suggested that extreme El Niño events will increase under future warming. In fact, the later paper found these events will continue to increase in frequency over the next century, even if global warming is limited to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius at most.

But these papers focused on the rainfall associated with El Niño events, a slightly less direct way of looking at the question. They also inspired some debate among climate scientists about how much certainty the findings could carry. According to Trenberth, that’s because the models still need some improvement when it comes to simulating the behavior of El Niño.

The new study, he said, is the “most credible analysis” yet.

But Cai notes that the basic conclusion in his most recent paper is still similar to the previous studies—that strong El Niño events will probably happen more frequently as the climate warms. And if that’s the case, then the weather events associated with these El Niños may also become more intense, as well.

But climate change may affect more than just the severity of El Niño events and their consequences. Some research has also suggested it may increase the total area across the globe affected by El Niño. So when El Niño occurs, it may affect the weather in even more places than it already does.

A 2017 paper found that, under a business-as-usual climate scenario, the amount of land area in the Southern Hemisphere affected by El Niño-driven precipitation changes may expand by 19 percent. The area affected by temperature changes, such as temporary El Niño-related warming, may increase by about 12 percent.

A highly variable past

These are all effects scientists say may occur over the next 80 or 100 years. Whether El Niño has already begun to shift in response to climate change is even more difficult to investigate.

Because the ENSO cycle shifts only every few years, and because El Niño events are so diverse to begin with, scientists need to examine a very long record of data to determine whether there have been any clear trends.

According to Stevenson, the UC Santa Barbara scientist, “you need something like 250 to 300 years in order to be sure that you have sampled all the statistics of what El Niño wants to do.”

Scientists have been able to use some indirect methods to investigate El Niño events hundreds of years in the past. A 2013 study, led by Kim Cobb of Georgia Tech, analyzed ancient fossilized corals, which can contain chemical information about the condition of the ocean centuries or even millennia ago. In this way, researchers were able to reconstruct the ENSO cycle going back 7,000 years.

They found that ENSO events have seemed more variable than average starting in the 20th century. But when they’re considered in the context of the entire long-term record, it’s not unprecedented.

Overall, the study found the ENSO cycle is so temperamental, it would be difficult to detect any changes caused by a single driver, whether human or natural.

Andrew Wittenberg, an El Niño expert with NOAA, pointed to some of his own recent papers that have come to similar conclusions. After the severe 2015-2016 event, he and other scientists became interested in whether it was unusual in any way, compared with the long-term record.

A 2018 paper he co-authored, led by fellow NOAA researcher Matthew Newman, found that the event was “strong, but not unprecedented.” It was the kind of event that would be expected to occur every few decades or so—although warming in the Pacific Ocean has otherwise certainly been influenced by climate change.

They also found the continued need for improvement in the ENSO models makes it difficult to say whether there’s been any change in El Niño driven by global warming over the last century. So while global temperatures have clearly been rising for the last 150 years, their influence on this particular natural climate phenomenon—so far—remains unclear, and may even be yet to emerge.

Understanding the interactions between El Niño and the warming climate, though, is likely to become more and more important in the future.

As far as natural climate cycles go, El Niño already has some of the most pronounced influences on global weather. And if those effects become stronger or affect bigger areas in the coming decades, human communities around the world could benefit from the ability to anticipate them and prepare accordingly.

For now, it may be most fair to say that while uncertainties still persist around El Niño, certain kinds of changes are surely coming, Stevenson said.

“The fact that we don’t know exactly how big El Niños will be in terms of their sea surface temperatures doesn’t mean we don’t know anything about how their impacts might change,” she told E&E News. “Most of the recent research has suggested that for a given El Niño, the kind of bang for your buck for that El Niño will increase.

“Things like more rain, more heat waves—whatever the El Niño wants to do now, it will do more of in the future as a result of this background warming, as a result of climate change.”

Reprinted from Climatewire with permission from E&E News. E&E provides daily coverage of essential energy and environmental news at www.eenews.net.