Ed. note – This story has been updated to reflect that the Alberta Health Services list of Canadian communities with low immunization rates is from 2014.

Harper Whitehead was just seven days old when her mother noticed something was wrong.

“She had a little bit of a cough and her feedings were starting to decrease,” recalls Harper’s mother, Jessica Whitehead.

The Whiteheads had been living with Jessica’s parents in the rural community of Picture Butte, Alta., a small farming town just north of Lethbridge. In 2012, about 1,700 people called the town home. The crime rate was low and people knew their neighbours. Whitehead never imagined her baby daughter would be in danger there.

“It was day 10 that she actually went into the hospital. She was instantly admitted and hooked up to oxygen and by the end of day, she was airlifted to the (Alberta) Children’s Hospital in Calgary.”

Harper had whooping cough, also known as pertussis. It’s a vaccine-preventable illness that for infants is often deadly. In Alberta, children can’t be vaccinated against pertussis until they are two months old, so Harper was completely vulnerable to the infection.

WATCH: The WHO calls vaccine hesitancy one of the top 10 biggest threats to global health. The reluctance or refusal to accept vaccines has led to a resurgence of diseases once thought to be a thing of the past. Heather Yourex-West looks at the Canadian communities most at risk.

She also happened to be living in a community where immunization levels were so low that there was no herd-immunity protection available for her. Herd-immunity protection happens when enough of a population is immunized against a disease for those unable to be immunized (like a newborn infant) to be protected. For a disease like pertussis, a 94 per cent immunization rate is required.

READ MORE: Strong majority of Canadians support mandatory vaccinations for children entering school, poll says

“To watch it take over a little body is very surreal. You don’t want to believe it’s as serious it is,” Whitehead said.

“I just remember knowing that I was going to lose her, that whooping cough was going to win this one, and I just wanted to hold my daughter as she passed.”

Harper died less than a month after being born.

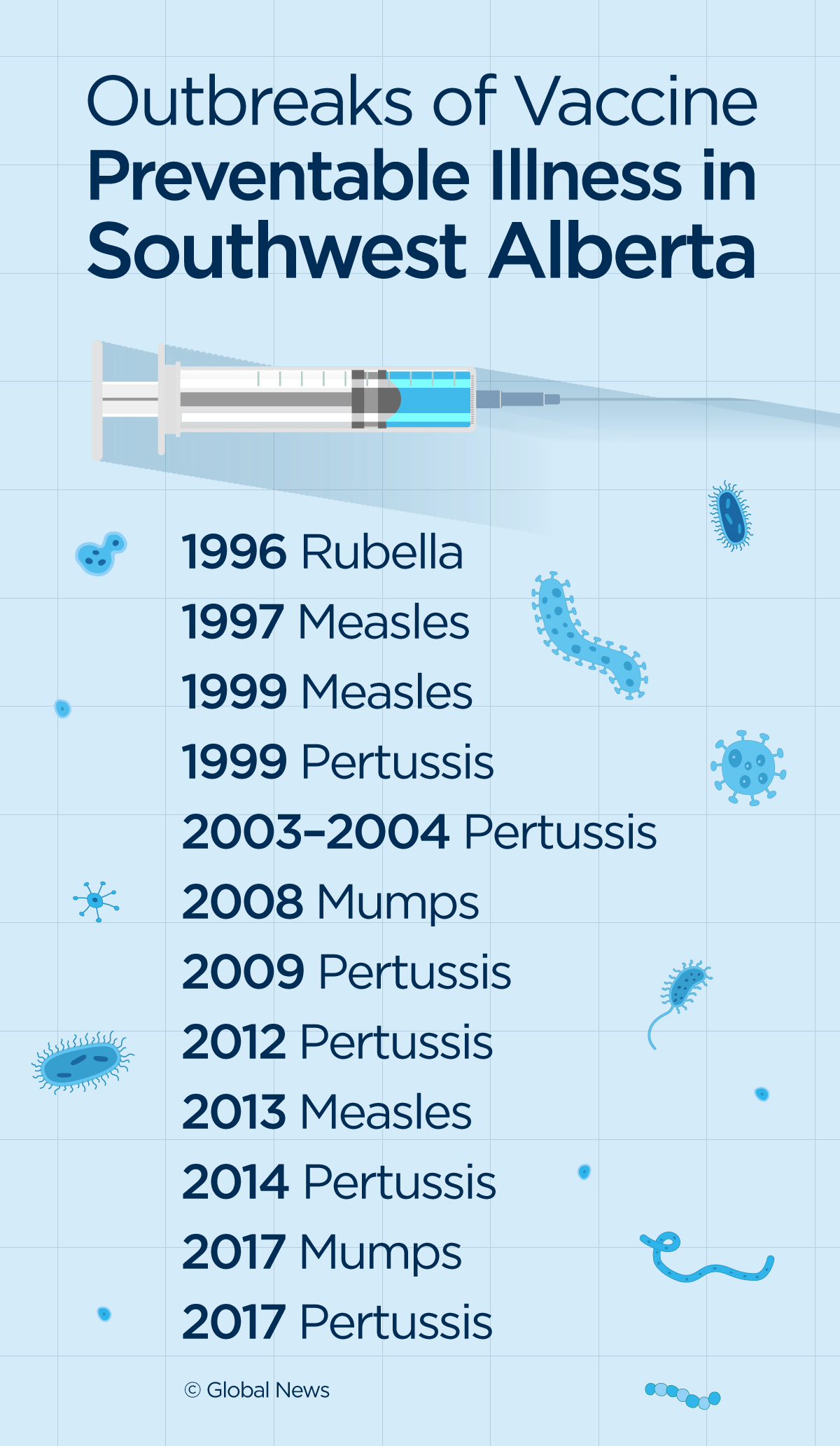

A horseshoe-shaped area around Lethbridge, Alta., has seen 12 different outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. They include a rubella outbreak in 1996; measles outbreaks in 1997, 1999, 2013; a mumps outbreak in 2017; and six outbreaks of pertussis/whooping cough between 1999 and 2017.

“In southern Alberta, immunization uptake between children varies between communities and schools. We have some schools with 10 per cent of children immunized, and others with 90 per cent,” said Dr. Vivien Suttorp, medical officer of health for Alberta Health Services south zone.

READ MORE: More U.S. measles cases so far this year than in all of 2018

Dr. Suttorp says the reasons why immunization rates are low in the region are complex. Religious and cultural beliefs play a role, but across Canada, this community is not unique. Health officials have identified a number of other places across the country that are vulnerable to outbreaks because they are largely unprotected.

According to a 2014 Alberta Health Services presentation, those communities included Norwich (Oxford County), St. Catharines and Brantford in Ontario; the Lower Fraser Valley, Smithers and Vanderhoof in B.C.; and the Lacombe, Rimbey, Red Deer and Lethbridge-areas in Alberta.

Since then, surveillance data suggest vaccination coverage rates has dropped even further areas in some areas. According to Alberta Health, within the county of Lethbridge, 68.5 per cent of children had received the MMR (Measles, Mumps and Rubella) vaccine in 2014, and by 2017 that rate had fallen to 64.5 per cent.

Data from the BC Centre for Disease Control suggests a similar trend. Within the Northern Health region (which contains the communities of Smithers and Vanderhoof), 65 per cent of children were considered up-to-date with their vaccinations in 2014. By 2017 that number had fallen to 63 per cent.

“I think a big part of public health is surveillance, looking at data,” Dr. Suttorp said. “Where are the diseases in the world? Where are diseases in Canada? What are our immunization rates?”

The problem is that across the country, the picture is incomplete. Immunization tracking falls under the jurisdiction of Canada’s provinces and territories and there are no national standards in place.

READ MORE: What we can learn from the current measles outbreak in B.C.

“For public health purposes, definitely more work needs to be done in order for us to tell where the pockets of under-immunization are,” said Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer.

Seven years after losing her daughter, Whitehead says it’s difficult to hear about anyone choosing not to vaccinate their children and she fears for other families who may be put at risk.

“I can see the things that Harper could be doing and should be doing and would be doing and how big she would be today … but I don’t get to experience that with my own daughter. It’s really hard.”

This is the first story in ‘Unvaccinated: Canada’s Public Health at Risk’, a Global News series on the challenge Canada faces from dropping vaccination rates. Tuesday: How did we get into this mess?

UNVACCINATED, Part 2: How ‘vaccine hesitancy’ became a threat to public health

UNVACCINATED, Part 3: Should vaccinations be mandatory for school-aged kids?

UNVACCINATED, Part 4: A former vaccination skeptic warns of online misinformation

_848x480_1467870276001.jpg?w=1040&quality=70&strip=all)

Comments