Are Philippine children’s deaths linked to dengue vaccine?

- A mix of corporate greed and corruption is being blamed for a series of deaths linked to pharmaceutical giant Sanofi’s Dengvaxia vaccine

- People’s trust in country’s immunisation programme is shaken, leading to a surge in measles cases

In suburban Taytay, a 20-minute drive from downtown Manila, in the Philippines, a distraught family have gathered at a funeral parlour. At the back of the building, in a wide, white-tiled room, the body of a 12-year-old boy lies on a stainless-steel table, face up, legs slightly bent. Five forensic investigators put on blue plastic overalls before they cut open Elijah Rain de Guzman to perform an autopsy. Over almost four hours, they collect tissue samples, measure and weigh the major organs and carefully photograph every detail. Outside, Elijah’s family are waiting.

Scenes such as this, which took place in September, have become routine for Dr Erwin Erfe, a forensics expert working for the Philippine Public Attorney’s Office. For many months, he has been performing two or three autopsies every week on the bodies of young people who exhibited “internal bleeding, especially in the brains and lungs … and swollen organs”.

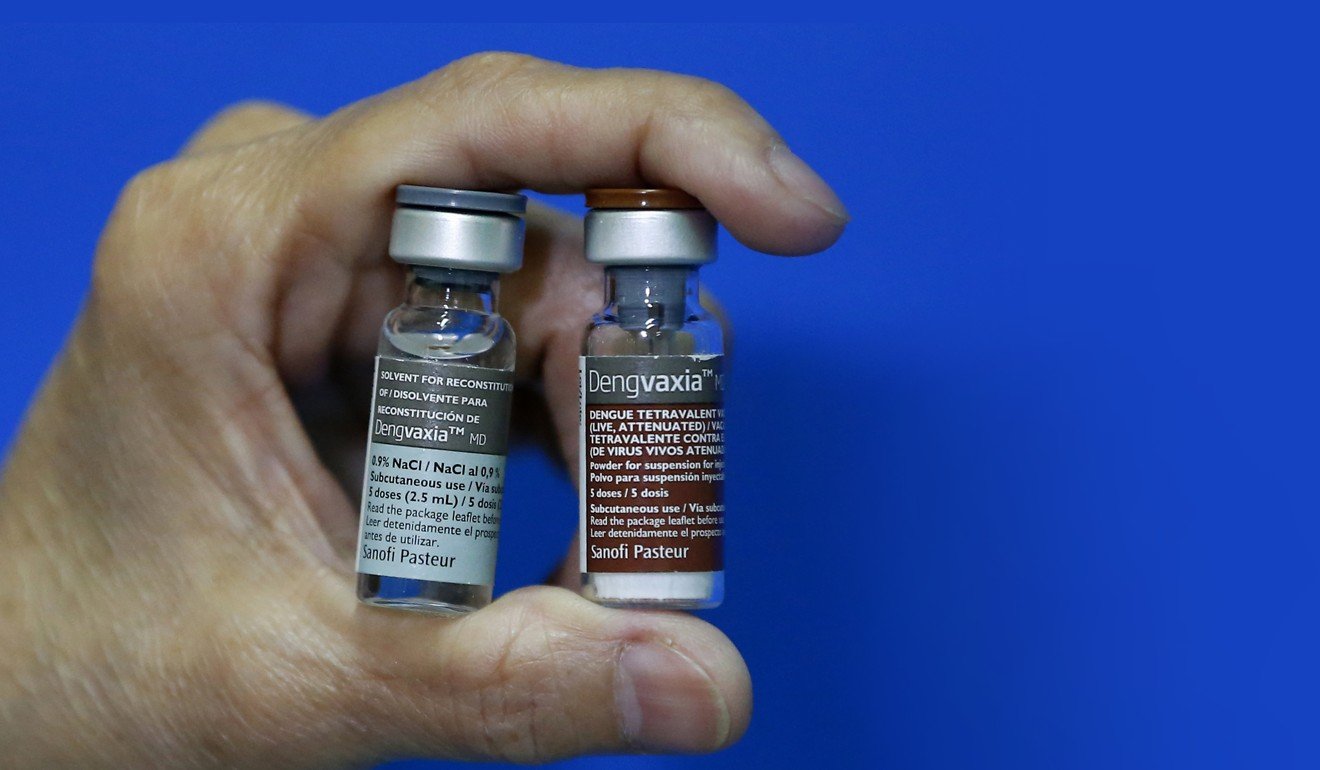

Erfe and his colleagues believe these symptoms have been caused by Dengvaxia, a dengue vaccine developed by French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi. He has performed 132 autopsies that point to the vaccine as a probable cause of death.

“Some have died quickly after the injection, especially the children who had compromised immune systems, others developed an infection several months after,” he explains.

Most have come from a poor background, without easy access to the health care system.

In total, the deaths of about 600 children who received Dengvaxia are under investigation by the Public Attorney’s Office.

Dengue is spreading rapidly around the world, infecting 390 million people every year – 100 million of whom develop symptoms, with 500,000 of those contracting haemorrhagic fever – and killing 20,000, mostly children and pregnant women.

Spread by mosquitoes, the dengue virus can cause what is sometimes known as break-bone fever, so called because it feels to the sufferer as though their bones are breaking. Death is caused by either organ failure or excessive bleeding, usually in the gastrointestinal tract.

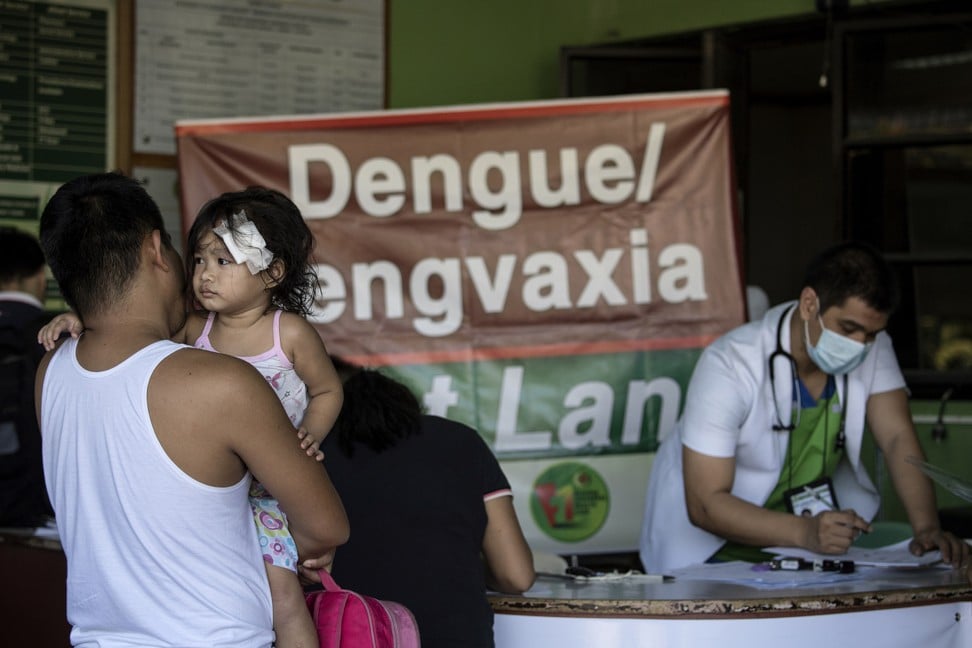

In the Philippines, the disease has placed a huge financial burden on the health care system, and so, between April 2016 and November 2017, Dengvaxia was administered to more than 800,000 children across the country.

The vaccine, it turns out, protects only those who have already been infected with one of the four strains of the disease. For the others, the seronegatives (about 10 to 15 per cent of the vaccinated children, according to estimates from the World Health Organisation [WHO]), the vaccine actually increases their chances of getting sick if infected with the virus. No tests were performed on individual Philippine children to see whether they had been exposed to the virus before vaccination. In other words, between 80,000 and 120,000 of them are now more at risk of death if they contract dengue than they were before they had been vaccinated, and health authorities have no way of knowing who they might be.

Adding to the confusion, Dengvaxia is believed to have another deadly side effect. According to Erfe and chief public attorney Persida Rueda-Acosta, some of the children have died from viscerotropic disease, a general failure of the organs, an effect of one of the components of the vaccine. In a document sent to the Philippine Department of Health (DoH) before the procurement, Sanofi mentioned viscerotropism as a potential risk, but stated that no cases had been observed during clinical trials of Dengvaxia.

The increased risk to seronegatives is due to a singular mechanism of dengue, known to scientists for several decades: antibody-dependant enhancement (ADE). Once a person is infected by one of the four strains of the disease, they are immune to that particular strain for the rest of their life. But, in the case of a second infection, by another strain, the antibodies developed to fight off the first infection might become “double agents”, helping the new infection to pass through the barriers of the immune system.

Sanofi calls this “a theory”. However, “the phenomenon is now quite well documented, you cannot call it a theory any more”, counters Professor Scott Halstead, 88, who is one of the world’s foremost experts on dengue fever. By mimicking a first infection, the Dengvaxia vaccine makes some seronegative children more vulnerable in the event of an attack, instead of protecting them.

[The Dengvaxia] trials were riddled with small inaccuracies, missing data, uncalculated risks […] Not really a high-level manipulation of data, but more the work of obliging statisticians who want to please their bosses

In Sanofi’s clinical trials, ADE was seen to be a higher risk for younger children: those under five were almost eight times more likely to contract a severe form of dengue after receiving the shot than the children in the control group, who didn’t receive the shot. Sanofi, however, explained this as being an “immature immune response” and set the minimum age at which children should receive the vaccine at nine years old.

“This is not biologically sensible,” Halstead claims. “When they are nine years old, children have statistically more chances to have been previously infected than the very young ones. But the risk remains for all seronegative children, regardless of their age.”

Halstead tried to warn Sanofi and the Philippine authorities of his concerns, but to no avail. He sent a video explaining the potential risks of the vaccine to a local contact, hoping it would be broadcast in the Philippine Senate, which it was, finally, but only during a hearing held to identify where responsibility for the Dengvaxia mess lay.

Antonio Dans, with his wife, Leonila, led a social-media campaign to inform the public about risks associated with the vaccine. The couple are doctors and epidemiologists, working at the Philippine General Hospital – also a teaching institution – a beautiful colonial building on a busy street in old Manila. Dans specialises in cardiovascular disease but is also a skilled statistician, and teaches his students to detect anomalies in trials and reports published by the pharmaceutical industry.

“[The Dengvaxia] trials were riddled with small inaccuracies, missing data, uncalculated risks …” he says. “Not really a high-level manipulation of data, but more the work of obliging statisticians who want to please their bosses.”

Why weren’t these voices heard?

“There had been a worldwide eagerness to find a vaccine, for a very long time,” Halstead says. Dengue fever was identified as early as the 18th century, but attempts to produce a vaccine had failed. Halstead says there was a global sense of relief when Sanofi at last found a vaccine that appeared to work reasonably well.

In March 2016, the WHO published a detailed assessment of Dengvaxia, stating that “there is a theoretical possibility that vaccination may be ineffective or may even increase the risk in those who are seronegative at the time of first vaccination”, but gave a green light for its use in the most affected areas of the world.

For Dans, the problem lies in the contents of the final report compiled by Sanofi and a lack of skilled statisticians in government teams to read past the marketing blurb.

“The same company, Sanofi, is designing the trials, performing them, assessing them, writing final reports … and sells the vaccine? Of course, there was a high conflict of interest. The system must change, if we don’t want this situation to happen again,” Dans says.

When the crisis flared up it became very difficult to talk with Sanofi. They gave us the silent treatment

Sanofi’s main line of defence is to point out that none of these problems have occurred in the 20 other countries, including Singapore and Thailand, where Dengvaxia has been authorised. However, in all but one of those countries, the vaccine has been licensed for the private sector only, and is used by physicians on specific patients, with the possibility of prior screening for dengue infection and a medical follow-up if any infection occurs.

The only other country that has had a public anti-dengue programme, Brazil, rolled it out in only one province, and mostly on 15- to 27-year-old recipients. The Brazilian authorities worked closely with Sanofi on the design of the vaccination campaign.

In the Philippines, by contrast, “when the crisis flared up it became very difficult to talk with Sanofi”, remembers a bitter Janette Garin, who, as the nation’s secretary of health (from February 2015 to June 2016), was in charge of the anti-dengue programme.

“They gave us the silent treatment. So I started to talk with my counterparts in Brazil. It appears they were much better prepared,” she says, when we meet in a Japanese restaurant in Manila.

Furthermore, the clinical trials showed, Dengvaxia had always achieved better results in South America.

At the time of its launch, in 2014, Dengvaxia was billed as a scientific triumph on which Sanofi had spent “20 years of research and US$2 billion”, according to a company press release.

“Sanofi is all about what they invested in this vaccine, but they actually bought it from a start-up, as is the trend today in the pharmaceutical industry,” says Anthony Leachon, a physician and director of the government-owned Philippine Health Insurance Corporation.

The first dengue vaccine was, in fact, developed by a team of molecular biologists at Saint Louis University, in the United States. British biotechnology company Acambis acquired the rights to develop the vaccine. Once the vaccine began to look promising, in 2008, the company was bought by Sanofi, for about US$550 million.

Sanofi also invested in a new US$480 million factory in Neuville-sur-Saône, near the multinational’s headquarters, in Lyon, France. The infrastructure investment was the company’s biggest to date, and was made long before any clinical phase III trials (those conducted on humans) were undertaken.

Antoine Quin, director of the new pharmaceutical complex, called the move an “industrial bet”. During a hearing at the Philippine Senate in December 2017, Thomas Triomphe, Sanofi’s head of product strategy, declared that “this kind of anticipative investment is perfectly normal in the pharmaceutical industry”.

Halstead sees the move as being typical of the frenzied competition that exists between pharmaceutical firms, which are willing to take tremendous risks to be first into a lucrative new market: “They want to design vaccines before even understanding how the virus works.”

In Lyon, Sanofi’s management were under increasing pressure to sell a product in which the company had invested so heavily. Expectation mounted further in 2015, following the appointment of Olivier Brandicourt – who specialises in infectious and tropical diseases – as chief executive. He flagged Dengvaxia as a priority project.

Not everyone was convinced by the new product – French health authorities, for instance, have not recommended it for use in their overseas territories – and although the vaccine was given the green light in several countries, sales didn’t take off. Safety considerations aside, there were questions over the efficacy rate of the vaccine, which in Asian children is only 56 per cent after two years (meaning almost one child in two isn’t protected at that stage even after receiving a three-shot course) and rapidly wanes thereafter.

In November 2014, Sanofi’s senior vice-president for Asia, Jean-Luc Lowinski, met with Benigno Aquino, then president of the Philippines, at the Philippine embassy in Beijing, during that year’s Apec summit. Aquino acknowledged this during the December 2017 Senate hearing. Although the exact nature of the exchange remains unclear, a few weeks later, Sanofi submitted an approval request for Dengvaxia to the Philippine Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

A few months later, Garin, the freshly appointed director of the DoH and a protégée of Aquino, travelled to Paris and Lyon, where she visited the Dengvaxia factory.

“This is already questionable,” says Paulyn Ubial, an official at the DoH who was briefly health secretary after Garin. It may seem prudent for a health official to sound out the producers of a potentially life-saving drug but, Ubial says, the relationship was too cosy. “The secretary of health cannot appear with leaders from the pharmaceutical industry, that’s unethical.”

Asked about the trip now, Garin says she can’t remember much, just that she “slept a lot in the car, and visited some churches, but I can’t remember which ones”. According to a report by the Philippine embassy in Paris, during a dinner at a restaurant on the Champs-Élysées, she discussed the price of Dengvaxia with several Sanofi managers.

The price was set at 5,000 pesos (then worth HK$870) per dose in the private sector, 1,000 pesos for the government, which intended to give 1 million children a course of three doses each. This was “an outrageously inflated price”, according to Dr Francis Cruz, a former consultant to the DoH turned health activist, “especially given the fact that some doses were close to expiry”.

In January 2016, upon her return from another visit to Paris, Garin unveiled a 3.5 billion pesos (then worth HK$609 million) anti-dengue programme.

“I remember almost falling out of my chair when I learned about the budget of the dengue programme,” recalls Dans. The amount is higher than that devoted to all other vaccination programmes in the country combined – including those for measles, polio, Japanese encephalitis and human papillomavirus (HPV); even though dengue is not among the top 10 causes of death in the Philippines.

This is a case of “misplaced priorities, at best”, says Leachon.

The deal was plagued by irregularities. Procurement rules were violated, according to a report by the Commission on Audit, and vaccine doses had arrived in the Philippines even before a contract was awarded. Garin appointed herself director of the FDA for six months, on May 5, 2015, just 10 days before accepting Sanofi’s invitation to visit its Dengvaxia facility in Lyon.

The anti-dengue programme was officially budgeted at 3.5 billion pesos, but the contract with Sanofi was for 3 billion pesos. For almost two years, the extra 556 million pesos remained unaccounted for, until press in the Philippines began to ask uncomfortable questions. The missing sum reappeared in the DoH budget in January 2018 and it was said to have “transited” through a programme to improve the state of hospitals in the country.

That same month, Sanofi reimbursed the DoH to the tune of about 1.2 billion pesos for unused doses. The pharmaceutical company denied the reimbursement was a reflection on the quality of its product, but said it “hopes that this decision will allow us to be able to work more openly and constructively with the DoH to address the negative tone towards the dengue vaccine in the Philippines today”.

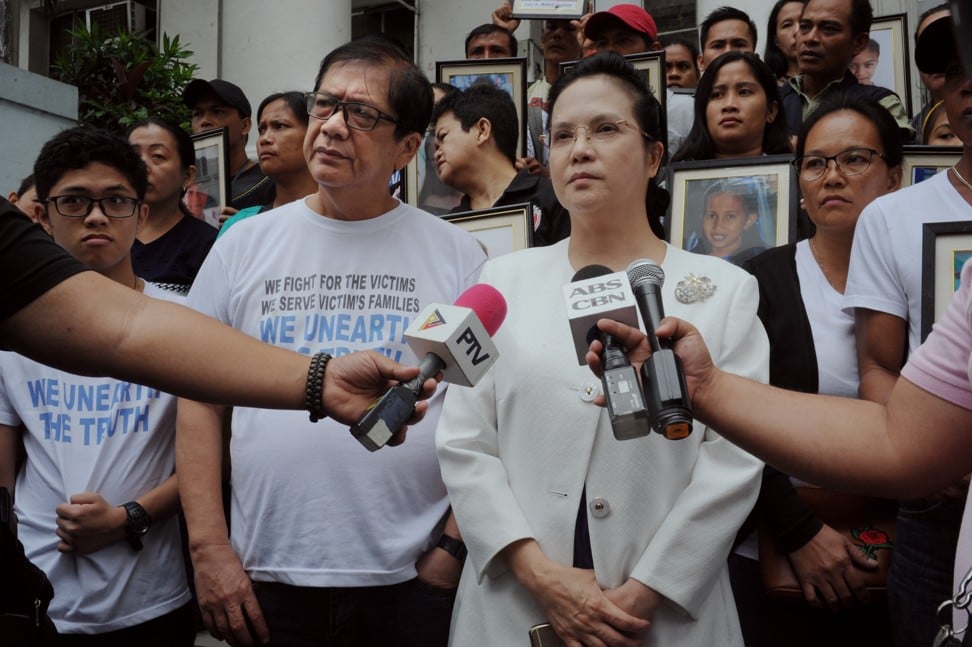

Rueda-Acosta is suing 39 people, including six Sanofi representatives, for “reckless imprudence resulting in homicide”. “It’s greed that killed those children,” she says angrily.

Another legal complaint, for plunder and malversation of public funds, has been filed at the Office of the Ombudsman against Garin and Aquino.

Besides the financial interests at stake, it is believed there was a political aspect to the vaccination programme.

“It was made clear the vaccinations had to begin during the [2016 presidential] campaign,” claims Ubial. And the three provinces chosen for the launch of the programme were not among those most affected by the disease, but “the ones who had highest number of voters among affected regions”, according to the DoH official. On launch day, April 4, 2016, vaccinated children were given yellow T-shirts, the colour of the ruling Liberal Party, to wear as they posed for press photographers.

Because of a tight agenda, the announcement of the anti-dengue programme having been made in January, with the election in May, the establishment of the programme was rushed, it’s contended.

“It was madness,” reflects Ubial. “Normally, with a new vaccine, we need one to two years to prepare the health sector, and we start with a target population of about 40,000 individuals.”

Professionals in health centres were not trained to screen out children with weakened immune systems; several children with lupus, leukaemia or other severe chronic conditions were given the shot.

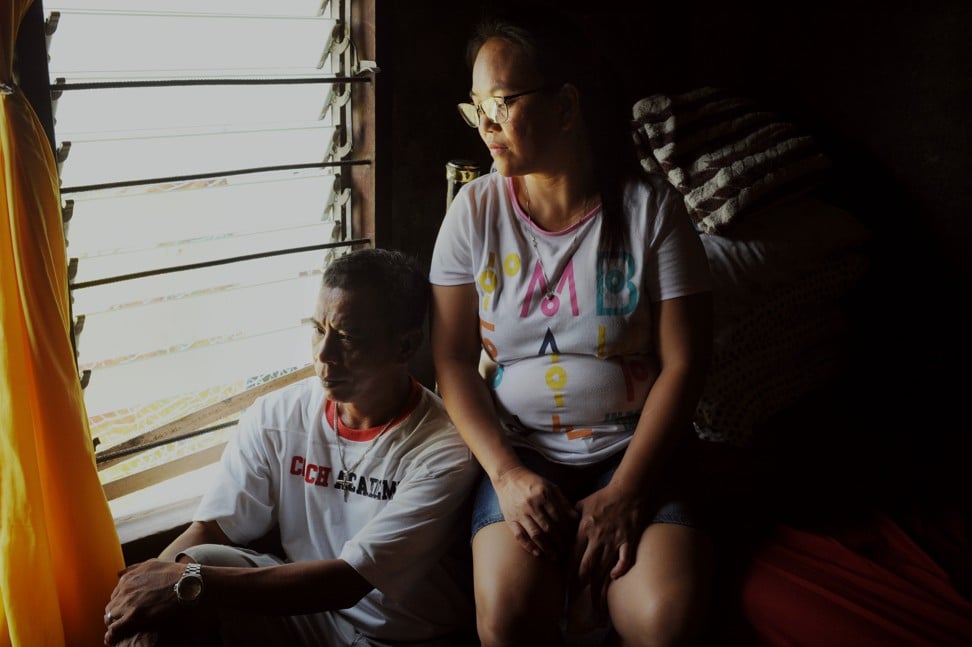

“Maybe my son would have died from his tumour any way,” says Romeo Cariño, father of 12-year-old Roshaine, who died last February in Minalin, Pampanga province. “But I could have had a few more months, maybe a few more years with him.”

Rueda-Acosta believes both the vaccine and the hasty implementation of a “massive and indiscriminate” vaccination campaign are to blame for many of the casualties.

Several children could have been saved if they had been treated in a timely manner, according to doctors. “My daughter was refused access to a hospital because she looked too poor,” says the mother of Riceza Salgo, 12, who had received the vaccine but developed dengue fever. “She could barely stand.”

Last March, the family, who live in Silang, Cavite province, eventually found a hospital that would take her, but Riceza quickly succumbed.

“This is not really fair,” says Cruz. “The measles outbreak is a worldwide phenomenon.” As is misinformation about the measles vaccine.

Nevertheless, it seems likely Dengvaxia has not only claimed the lives of children who may otherwise have been spared the worst excesses of dengue fever, but also, thanks to the ensuing scare, helped raise the death toll from measles in the Philippines.