Op-Ed: Climate change could bring bubonic plague back to Los Angeles

The steamship caused the last global outbreak of bubonic plague. Climate change could cause the next one.

Longer, hotter weather patterns are extending the breeding season of rats and rodents, leading to a steep increase in their numbers in places like Los Angeles, New York and Houston. Over the last decade, urban rat populations are up by 15% to 20% worldwide, thanks to a combination of climate changes and a greater preference among humans for urban living, increasing the amount of trash available for scavengers, according to estimates from Bobby Corrigan, a rodent control consultant and one of the nation’s leading rat experts.

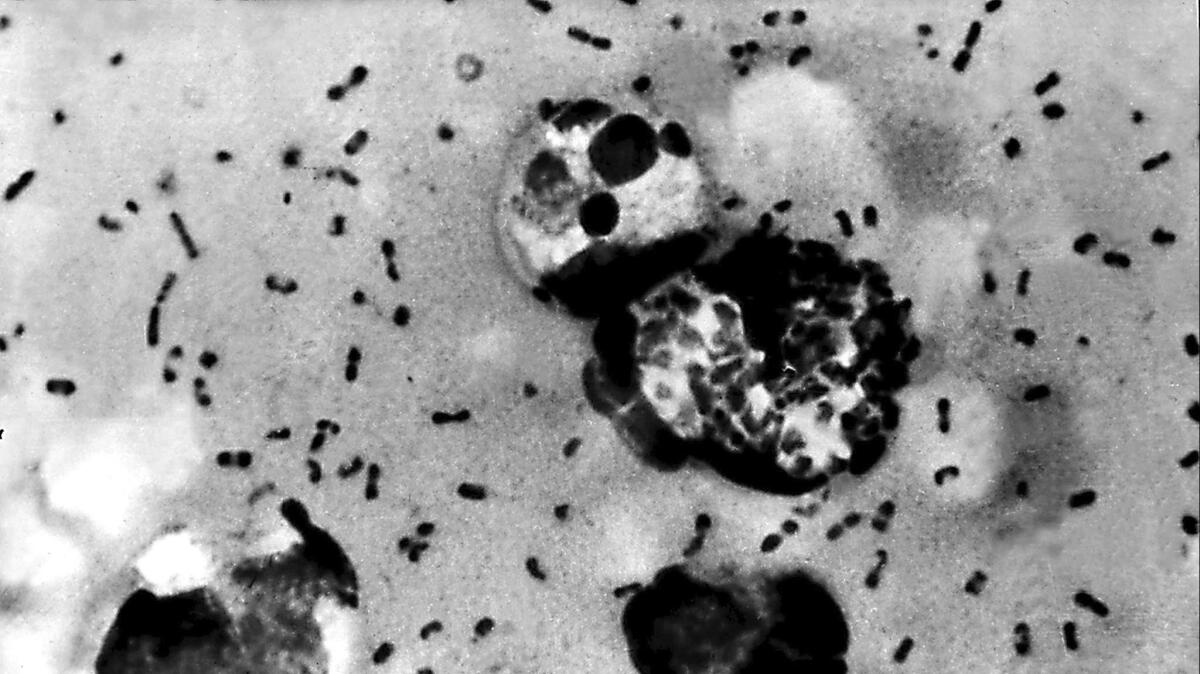

The swelling number of rodents isn’t just an urban nuisance. More importantly, all those additional rats and squirrels can serve as hosts for fleas carrying the plague-causing bacterium Yersinia pestis. The disease is already endemic among fleas that feast on rural squirrels in California, Arizona, Wyoming and other states. Climate change could make it possible for plague-carrying fleas to thrive in more places than they do now, bringing the disease into closer contact with humans.

“Any climate change conditions that increase the number of fleas [also increase] the distribution of plague,” said Dr. Janet Foley, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at UC Davis.

Already, public health officials increasingly find themselves battling rare and dangerous diseases associated with rats. An employee at Los Angeles City Hall who recently contracted typhus blamed the disease on flea bites she suffered as a result of the building’s rat infestation, while a cluster of patients suffering from the rare disease leptospirosis, an often-fatal condition spread by rat urine, were identified in the Bronx in 2017. An outbreak of bubonic plague due to contact with diseased squirrels prompted Russia to close its border with Mongolia last week.

While many major cities face increasing rat populations, L.A. finds itself in unique danger of disease because of its rapidly growing homeless crisis.

While many major cities face the problem of increasing rat populations, Los Angeles finds itself in unique danger of disease because of its rapidly growing homeless crisis. As more people live in closer contact with rodent fleas that can carry the plague bacterium, preventing an outbreak of one of the most frightening diseases in human history will require a stronger push to eradicate potential hosts.

Eliminating rats and squirrels to save human lives saved Los Angeles once before. In 1924, fleas from an infected rat bit a man named Jesus Lajun who lived on what was then called Clara Street, near the current-day Twin Towers Correctional Facility downtown. Within six weeks, nearly everyone who had come into contact with Lajun during the roughly 48 hours between the time he caught the disease and the time he died from it was dead. The trail of victims included not only his immediate family members but also those of a neighbor who cared for him when he was too weak to leave the house.

Panicked health officials quarantined an eight-block area surrounding the mostly Mexican American neighborhood as the outbreak swelled to claim nearly 40 lives, while businesses across the city fired Latino workers out of a misplaced belief that they were more likely to carry the disease. Fearing the start of an epidemic that could spread eastward and kill millions, as had outbreaks in China and India, U.S. Surgeon General Hugh S. Cummings sent a federal health officer named Rupert Blue to Los Angeles to contain the disease.

Some 20 years earlier, Blue had been an officer in the Marine Hospital Service when a steamship carrying infected rats from China sailed through the Golden Gate, bringing plague to North America for the first time. Soon, more than 200 people were dead in San Francisco as politicians, doctors and the editors of the state’s most powerful newspapers conspired to deny the reality of the outbreak. It was only after Blue demonstrated that a combination of killing rats and instituting sanitation measures to starve rodents of food had eradicated the disease from Chinatown did San Francisco finally take the steps to save itself. Blue and his team were ultimately responsible for killing more than 2 million rats, a figure five times greater than the city’s human population.

He followed a similar plan to save Los Angeles. Doctors under his command discovered plague-infected rats in an area from Beverly Hills to the Port of Los Angeles. Just as he had in San Francisco, Blue focused on not only the hard science of epidemiology by charting the path of the disease, but also on the soft science of persuasion, meeting with every civic group that would have him to spread the gospel of rat elimination. Within one year, more than 200,000 rats and squirrels had been killed throughout the city, and Los Angeles was once again free of plague, marking the last major outbreak of the disease in the country.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

Yet plague never truly left California. A plague-infected squirrel found in the Angeles National Forest prompted the U.S. Forest Service to close the Los Alamos Campground for 10 days in 2010. The last confirmed cases in the state occurred in 2015, when two visitors to Yosemite were diagnosed with and recovered from the disease. An average of seven people contract the disease in the U.S. each year. So far in 2019, cases have been identified in pets in Wyoming and New Mexico.

If plague moves into new areas where doctors and veterinarians are not familiar with it, victims may not be identified until it is too late, Foley said. “If the distribution of the disease changes, people won’t know that they’re in an area of high risk and the initial symptoms of plague in people and animals are not very specific,” she said, allowing for it to be misdiagnosed at a time when it is the most virulent.

Eradication programs to kill rats and squirrels at a time when their natural predators like coyotes and snakes are declining due to human population growth may be what prevents another outbreak, said James Holland Jones, an associate professor at Stanford.

“It goes against our modern sensibilities, but there is nothing else to keep their populations bound,” he said.

It can be easy to overlook something as elemental as improving urban sanitation at a time when declining vaccination rates appear to be the most pressing public health need. But the recent outbreak of measles in the country highlights how complacency makes us vulnerable to illnesses that were once thought to have been safely confined to the past. By applying the lessons of the forgotten fight against plague to the new reality of climate change, we can prevent the most terrifying disease of them all from once again driving the country into panic.

David K. Randall is the author of Black Death at the Golden Gate: The Race to Save America from the Bubonic Plague.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.